Hanafuda

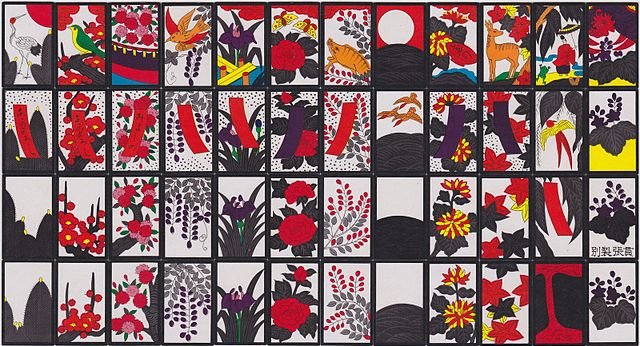

A complete set of hanafuda cards, arranged in order with January at the left through to December on the right. Each card is about a third the size of a Western-style playing card, but a lot thicker.

I bet you’ve played card games at some time in your life, and that it was with a deck of 52 cards plus jokers. Well, in Japan they use the same kind of cards, but they’ve also got their own deck called hanafuda, meaning ‘flower cards’, and they’re a bit harder to get your head around. Hanafuda cards are divided into twelve suits, one for each month of the year, but there isn’t much of a pattern to the way values are applied to cards within each suit – you just have to learn the meaning of each card individually.

Playing cards have a long history in Japan that goes back way before the first contact with Europe. In early times, card games were popular with the nobility, who considered them to be refined and sophisticated, but they were largely ignored by the common people. This all changed when the Portuguese missionary Francis Xavier turned up in 1549. While Xavier’s mission may have been to bring Christianity to the Japanese, the crew of his ship succeeded in bringing them playing cards. The key to the success of the Portuguese cards was that they were used for gambling, something that clearly appealed to Japanese commoners a lot more than the polite games the nobility liked to play. Thus the 48 card hombre deck that the sailors brought with them soon became popular throughout Japan.

The hombre cards hadn’t been around for long when in 1633 the shogunate initiated its policy of restricting foreign influence and trade, which extended to a ban on foreign playing cards. The response to this was to invent new Japanese decks of cards, but as private gambling was banned at this time, the shogunate imposed bans on sets of cards that were widely used for gambling. This led to a cat-and-mouse game: Whenever one deck of cards was banned, a new set would be invented and used until it in turn was banned.

Eventually the hanafuda cards emerged in the late 18th century. What made them stand out is that they’re a hybrid of traditional Japanese and Western styles. Like the European hombre cards, there are 48 cards that can be divided into twelve groups of four, but unlike European cards they have pictures instead of numeric values. This meant that they couldn’t be used for most of the gambling games that were popular at the time, allowing them to escape an official ban.

By this time, the relentless government bans had taken their toll on the popularity of card games, so hanafuda didn’t take off in a big way. This all changed in 1889, when Nintendo was founded specifically for the purpose of producing Hanafuda cards. (Yes, the same company that later produced the Game Boy and the Wii – but they didn’t produce anything other than playing cards until the 1960s.) Nintendo’s cards sold well, but were mainly used for gambling, which remained illegal. Hanafuda cards thus gained a strong association with the Yakuza gangsters who ran the gambling parlours, and many Yakuza have tattoos based on designs from hanafuda. Even today, hanafuda are strongly associated with crime and the underworld, a taint that deters many respectable Japanese people from playing with them.

This is how a game of koi-koi begins. Each player has eight cards in his or her hand, eight cards are face up on the table, and the rest are in the pack.

The insalubrious reputation of hanafuda seems very much at odds with the cards themselves, which emphasise the beauty of nature. Each of the twelve suits corresponds to a month of the year, and is identified by a seasonal plant, most of which are flowers in bloom. Starting from January, these are pinecones, plum blossoms, cherry blossoms, wisteria, iris, peony, bush clover, silver grass, chrysanthemum, maple leaves, willow and finally paulownia for December. (If you don’t know what some of these plants look like, take a look here.) If you want to play with hanafuda cards, you’ll need to learn to recognize which month each plant corresponds to, so you know its ranking compared to cards of other suits. As well as the plant indicating the month, some of the cards bear another symbol, indicating whether it’s a normal card (one point), ribbon card (five points), animal card (ten points), or a bright card (twenty points). Despite this system, the actual point value of the cards is irrelevant to most games – what matters is usually specific card combinations that gain points according to the rules of the game being played.

The whole hanafuda system is highly irregular – which combination of card types is present varies from suit to suit. Ten of the twelve suits have a ribbon card, four of which are plain red ordinary ribbons. There’s also a set of three blue ribbons (June, September and October), and a set of three ‘poetry ribbons’ with writing on them (January, February and March). The significance of the ribbons depends on which game you’re playing, but typically you score points for collecting a certain number of ribbons, and you get a bonus for having all three blue ribbons, or all three poetry ribbons. The writing on the March ribbon reads ‘Miyoshino’, the name of a town in Nara prefecture famed for it’s beautiful cherry blossoms, but there’s something very peculiar about the writing on the other two poetry ribbons. This reads ‘akayoroshi’ (using an archaic character for ‘ka’ that is no longer in use). What makes this odd is that this isn’t a word in Japanese, and no one knows what it’s supposed to mean. Despite this, it’s still faithfully reproduced on every set of hanafuda cards.

Nintendo have produced some special sets of hanafuda cards themed with Mario and other popular Japanese characters.

Now is where it starts to get really complicated. Nine of the suits contain an animal card, but the animal card for May is a bridge, and the one for September is a sake cup. The other seven animal cards do contain animals: a bush warbler, a cuckoo, butterflies, a boar, geese, a deer and a swallow. The problem is that three of the bright cards also contain animals: January has a crane, December a phoenix, and November has the tenth-century calligrapher Ono no Michikaze, together with a frog. The March bright card depicts a curtain, which is probably sheltering people who are admiring the cherry blossoms that also appear on the card, while the August card shows a full moon. In koi-koi, the most popular hanafuda game, if you get either of these cards together with the sake cup, you score extra points, presumably because sake is a traditional accompaniment to both flower viewing hanami parties, and to moon-viewing tsukimi ones.

Most suits have two normal cards, a ribbon, and either an animal or a bright card, but there are three exceptions. August has both an animal and a bright card, but no ribbon, November has a ribbon, an animal and a bright card, and December has three normal cards and a bright card. Perhaps the most confusing card of all is the November ‘normal’ card, which plays the role of wild card in many games. It’s called the lightning or devil card, and it doesn’t show the willow trees that identify the other cards in the suit. It reportedly depicts either the violent storms that Japan is prone to in November, or the devil with a drum. It doesn’t look much like either to me, so I’ll leave it to you to make your own mind up.

If you want to be good at hanafuda games, you need to remember which cards occur in which suit, so that you can work out what cards your opponent might have, and which cards are yet to enter play. Once you’ve made sense of the cards, you can then start to learn some games you can play with them. This usually involves memorizing specific sets of cards that score you points. For example, in koi-koi, getting the boar, deer and butterfly, will score you five points, but no other set of three animal cards scores you anything at all. By now, hanafuda may be seeming incredibly convoluted, but with a bit of practice you quickly become familiar with the cards, and they certainly have a charm that is missing from their Western equivalents.

Besides Japan, hanafuda cards are popular in several Pacific island nations, and in Hawaii. Korea has its own version of hanafuda cards called hwa-tu, which have a few differences, such as the November and December suits being swapped around, but unlike hanafuda, hwa-tu is a popular family game, free of nefarious associations. Also, beware that the rules of many hanafuda games vary from place to place, even within Japan. If you want to play yourself, you can buy hanafuda cards at Amazon. For a detailed explanation of how to play koi-koi, see here, and the rules for many other hanafuda games can be found here.

Trains Ninja